Friday, December 10, 2010

* The Duke! *

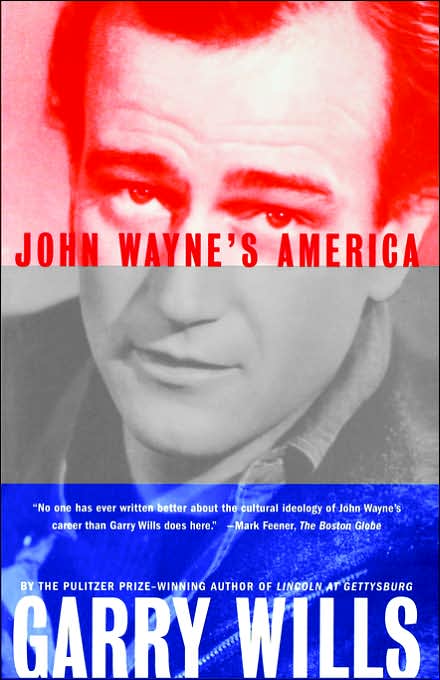

Memorializing the Deadly Myth of John Wayne

Posted on May 26, 2007

Hey, gunslinger:

John Wayne donned military gear in “Sands of Iwo Jima” (1949)

but he was missing in action on the real war front.

According to Gary Wills’ book “John Wayne’s America,” the man who portrayed the archetypal, battle-hardened Marine, Sgt. Stryker, in 1949’s “The Sands of Iwo Jima,” actually avoided the draft during WWII.

Wills contends that the Duke did not reply to letters from the Selective Service system, and applied for deferments.

Apparently, Wayne—who had sought stardom during years of B-pictures following Raoul Walsh’s 1930 frontier drama “The Big Trail”—got his big break during the struggle against fascism when many Hollywood action heroes like Tyrone Power enlisted and shipped out overseas.

Wills contends that the Duke did not reply to letters from the Selective Service system, and applied for deferments.

Apparently, Wayne—who had sought stardom during years of B-pictures following Raoul Walsh’s 1930 frontier drama “The Big Trail”—got his big break during the struggle against fascism when many Hollywood action heroes like Tyrone Power enlisted and shipped out overseas.

books.google.com

The Wimp Factor

The Wimp Factor

Lakshmi Chaudhry

AlterNet

October 29, 2004

The author of a new and timely book reveals how American politics is shaped by a cultural definition of masculinity that is based on disavowing all things feminine.

Tools

PR

Swaggering machismo got a new lease on life after the post-9/11 attacks, as Republicans tried to appropriate not just patriotism but also masculinity as a GOP virtue. Attacking the manhood of the opposition has become a signature tactic of any GOP election strategy. So it isn't surprising that the 2004 presidential election campaign has been played out over the past six months as a battle over John Kerry's masculinity. Be it his "sensitivity" on the war on terror or "girlie-man" preoccupation with the lack of jobs or health care, Kerry has been forced to defend himself from a barrage of rhetoric carefully designed to cast not just him but the entire Democratic plank as the epitome of feminine weakness.

As Stephen Ducat points out in his new book, "The Wimp Factor: Gender Gaps, Holy Wars, and the Politics of Anxious Masculinity," this obsessive focus with masculinity is hardly new. The penis was a major player even in ancient Greek politics. In the United States, politicians have long adopted a working class machismo to win popular support. Wonder where Dubya got his inspiration? You need look no further than Teddy Roosevelt, who was as much a faux cowboy as our current president.

A professor of psychology in the School of Humanities at New College of California, Ducat is a licensed clinical psychologist. "The Wimp Factor" draws connections between Mohamed Atta's last wishes, the electoral gender gap and environmentalism to paint a picture of a national psyche defined by a deeply flawed definition of manhood.

Ducat spoke to AlterNet from his home in San Francisco.

What is the central thesis of your book?

First let me throw out the term "femiphobia" as a way of naming this anxiety. Femiphobia is the male fear of being feminine. The underlying premise of my book is that the most important thing about being a man is not being a woman. This imperative to be repudiate everything feminine – whether it's external or internal – is played out as much in politics as in personal life.

In politics – where there is an enormous potential for personal gain or ruin – what this leads to is a concerted effort on the part of candidates to disavow the feminine in themselves, and to project it on to their opponents.

That was the central function of the Republican National Convention. Once you got past the moderate sweet talk, the purpose was essentially to make John Kerry their woman. There were a variety of subtle and not-so-subtle code words in this attempt to feminize him. This is a strategy that Republicans have long employed. They've just been more brazen about it lately.

In the book, you argue that this anxiety about the feminine defines not just American politics but has been a part of the history of Western culture.

The problem with our current notion of masculinity is that it’s a definition of manhood based on domination. The problem with definition of manhood based on domination is that domination can never be a permanent condition. It’s a relational state – it is dependent on having somebody in the subordinate position, which means that you may be manly today, but you’re not going to be manly tomorrow, unless you’ve got somebody to push around and control. This definition goes back to the ancient Greeks, and it makes masculinity a precarious and brittle achievement – which has to be constantly asserted. It has to be proven over and over again. It is the ultimate Sisyphean pursuit.

It has characterized politics going all the way back to the ancient Greeks. They had their own version of the "wimp factor." The worst thing an ancient Greek politician could be accused of is being a binoumenos, which loosely translated means "****ed male."

Manhood for the ancient Greeks – just as it is for us – was a difficult and transient achievement. It wasn't the gender that you had sex with that determined your masculinity, but what position you occupied in a relationship of domination. If you were penetrated, you were rendered essentially a woman. If you were the penetrator, then you were the man. In a way, we still hold that definition.

So is there anything unique in the way this "anxious masculinity" has taken root and developed in American political life?

In the United States, from the very beginning, if a politician wanted to attack the masculinity of a candidate, he would often accuse him of being aristocratic. The affectations of aristocracy were seen as markers of effeminacy. In a way that has very much informed what I describe in the book as the "wimp factor."

The term "wimp factor" is traceable to the representation of George Herbert Walker Bush in 1989 on the cover of Newsweek. Bush was a pampered patrician from an Eastern establishment family who was raised in the lap of luxury – which framed him as aristocratic. This was understood to be his primary political vulnerability, which was expressed in terms that are very similar to the concerns expressed in the 19th century.

Of course, in American culture, class is judged more in terms of style rather than anything empirical. So Bush [Senior] had a certain kind of artistocratic manner about him – he went to a truck stop and asked for "a splash" of more coffee. The incident made the news because it was judged to be an effeminate gesture.

So what I talk about in the book about the 19th century is the makeover that Theodore Roosevelt embarked on of himself – from somebody who is seen as an aristocratic dandy to becoming the "Cowboy of the Dakotas," as he liked to refer to himself.

He spent $40,000 dollars and bought property in the Badlands of South Dakota …

Just like Bush buying the ranch in Crawford.

Exactly. Like Roosevelt, both George Bush Sr. and George Bush Jr. tried to affect a geographic cure for their aristocratic origins. George W. was more successful. He was able to cultivate the accent and so on. He's been able to pull it off.

In American politics – both in the 19th century and in the present – it is a short step from seeming gilded to looking gelded. So there is an effort to adopt a persona of primitive masculinity. And the important thing to remember is that this is a makeover of style and not of substance. These are still wealthy members of the ruling elite, but their class is now camouflaged by virtue of this re-masculinization.

And so that's the big difference between American and, say, European politics, where being aristocratic is not necessarily seen as being feminine. Why is the working-class male seen as the epitome of machismo in a culture that's all about upward mobility?

In working-class culture, hyper-masculinity is understood more in terms with physicality, and it might be expressed in drinking, gambling, fighting, and so on. Over the years, this kind of working-class hyper-masculinity has been appropriated by those in the upper classes. It's seen as being more authentic because it's a more primitive expression of manhood.

Have you seen that movie "Fight Club"? That’s a movie about white-collar men who are unable to affirm their masculinity, [men] who live in a corporate hierarchy, and need to appropriate brutal pugilism that is their fantasy of working class masculinity. I think it relates, in part, to the inchoate sense that working as a paper shuffler, or as a bureaucrat, or in a cubicle, that there’s something unmanly about that. The popularity of boxing in the 19th century is actually about middle-class men who were drawn to the sport.

And so you see the kind of swaggering, cowboy pugilism among members of the elite like W. because that almost makes him seem like a regular guy.

Which in political life is very valuable. Absolutely. It helps to disguise his class privilege as well, allowing him to seem like an ordinary guy – something his father was unable to do.

This is where his inarticulateness actually becomes an advantage – because in American culture, there is a disdain for intellectuality. And that disdain is a gendered disdain – men who are intellectual are seen as somehow less manly. And so if somebody speaks too well, or too articulate, his masculinity is called into question.

That is why Kerry’s demeanor and facility with language has been problematic for him, while Bush’s dyslexia and inarticulateness and graceless use of language has actually been an advantage.

Let’s talk about the feminist revolution in this country in the 1970s. What impact does that have on the way gender plays out in politics?

We have the emergence in 1980s for the first time of the gender gap in political attitudes – men and women taking different political positions, voting for different candidates. Or, put another way, it’s when you begin to see the gendering of political issues where environmentalism is somehow female, or that being anti-regulatory is somehow male. The gender gap is the gendering of these political issues as masculine or feminine, which leads to men taking certain positions and women taking other positions.

This happens right after the decade which saw the big push for women’s rights.

It's right after the decade of the push for women’s rights, right after the decade of the only significant, military defeat in American history.

The fact that this defeat is understood by many in the culture as a psychological problem is evident in the fact that we actually have a pseudo-media name for it: “the Vietnam Syndrome.” We can understand the Vietnam Syndrome as a kind of wounded male self-esteem suffered by those who identify with a militarized nation-state and thereby feel humiliated vicariously in the defeat of the military in Vietnam.

Of course, in Vietnam, we weren’t just defeated by any enemy. We were defeated by an enemy that was largely viewed as somehow effeminate – you know, these little unmanly guys in black pajamas. They were constantly being derided in those terms, and yet they kicked America’s ***. And that was experienced as a profound humiliation.

So part of what we see in the 1980s is not only the emergence of the gender gap in politics, but also a whole new genre of war movies. These are movies in which hyper-masculine heroes win battles against the enemy once they throw off the shackles of the *****-whipped bureaucrats in Washington that won’t really let us kick the enemy's butt the way we want to.

Like Rambo?

Like Rambo, Chuck Norris, Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis – all these action figures. It all involves the same thing: rewriting the history of the Vietnam war, in so far that these movies focus on battles and ignore the actual loss of the war.

In the book you show how the gender gap emerges because of a shift in male attitudes in politics, not so much because of the women change their views.

Yes, exactly – and that is a major argument of my book. The gender gap is about men becoming more conservative. It isn’t about women becoming more liberal. Now, the feminist movement, in a way, did effect a kind of liberalization, especially when it came to issues of gender. But I think, in many ways, presented as another kind of threat to men. What you see is that men become significantly more conservative.

A Washington Post poll after the debate showed that 54 percent of men were supportive of Bush, where as only 49 percent of women [were]; Now that’s a 6 percent gap between men and women. But the more interesting gap is between groups of men. There was an 11 percent gap between the men that support Kerry and the men that support Bush. In other words, men are much more divided, if you will, than are women.

What was the difference between women?

Forty nine percent supported Bush and 47 percent supported Kerry. This is not that unusual. And again, women are pretty evenly divided, but men are not evenly divided. In other words, men are much more conservative than women are liberal.

What happened after 9/11? Did we regress or did hyper-masculinity in politics just become more obvious?

I think 9/11 was, in a way, Vietnam on steroids. I mean, 9/11 was a devastating horror, but it was also a humiliating atrocity, in addition to being a horrifying and disturbing one.

Part of what the attacks shattered was America’s phallic sense of invulnerability. You know, the sense that we don’t have to really think about anybody else. We are entitled to walk as giants across the globe and as one bumper sticker says in tongue in cheek, “What is our oil still doing in Iraq?” There’s this sense of a kind of omnipotence, of entitlement, of deserving privilege.

So for a brief period of time, there’s this kind of humility that comes over the country, but it quickly produces a kind of hyper-masculine backlash. It’s the revivication of a kind of primitive masculinity – the numerous kind of Chippendale-style calendars of firemen and policemen, the kind of conventional male heroes, which of course politicians wanted to appropriate.

All that rhetoric about how the "real men" are back?

You had all kinds of over-the-top, gushing encomia to this sort of post-9/11 revivified manhood. There was this special issue of the American Enterprise titled, “Real Men, They’re Back.” There was this article titled, “Return of Manly Leaders and the Americans Who Love Them.” There was even this contest where they had a chart of how Republicans and Democrats measured up and their conclusion was that to be a man you had to be a Republican. This is just one among numerous examples of the things that appeared post-9/11 period and prior to the invasion of Iraq.

If we understand the Iraq war as trying to assert masculinity after the trauma of 9/11, does that explain why the American public has been slow to accept that, perhaps, the war was a mistake?

One of the central features of what I call a phallic stance is the denial of weakness – the repudiation of dependency and the need for collaboration in all its forms. This is what we’re seeing. We have an administration that is, almost, congenitally incapable of acknowledging any mistake because to acknowledge a mistake is to really risk their manhood. To acknowledge a mistake, especially a mistake that involves failure to listen to advice – the proverbial refusal to ask for directions – imperils their manhood. And so, instead of this kind of behavior being pigheaded arrogance, it’s framed as manly resoluteness.

The Bush administration’s approach of swaggering masculinity appeals to this post-9/11 anxiety that you describe. But now we are in a war that is clearly a mistake. But during the campaign, it was far too risky for even John Kerry to admit that fact. So if he wins the election, do you think that the American public would be receptive to a Kerry administration saying after the elections, “This is a mistake, let’s find a way to get out”?

Yes, I think that it depends how it’s framed. He would have to frame it as a way of preserving American honor and that part of being honorable, and part of being effective in the world, is being able to learn from experience and being able to acknowledge one’s mistakes. I’m speaking of the American people as if they are a kind of a monolith, and different people would react differently. But I think there’s a majority – or plurality, at least – of people who would be able to accept it.

Right now, people are being lied to and they know they’re being lied to. But you have to reframe strength as truth-telling, as collaboration. So it would have to be framed in terms of strength, as opposed to acknowledging some shameful weakness.

~~~

Lakshmi Chaudhry is senior editor of AlterNet.

Article

GoogleBook

Revolutionary Characters

June 27, 2006

Books of The Times | 'Revolutionary Characters'

What the Founding Fathers Had That We Haven't

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

As the historian Gordon S. Wood notes in the opening pages of his illuminating new book, "Revolutionary Characters," Americans who look back on the Revolutionary War era and the lives of the founding fathers are frequently moved to ask, "Why don't we have such leaders today?"

The fledgling nation, after all, was fortunate enough to have an extraordinary assemblage of thinkers — including luminaries like John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton — whose vociferous arguments with one another helped shape the character of the new government. And the country was equally fortunate in having the right men around at crucial moments: Mr. Wood points out that it was the trust George Washington inspired in people "that enabled the new government to survive" its infancy, and he argues that "no other American could have done" what Benjamin Franklin did in bringing France into the war against Britain and extracting "loan after loan from an increasingly impoverished French government."

So why have the revolutionary generation's achievements — "the brilliance of their thought, the creativity of their politics" — gone unmatched since? Why was that political generation "able to combine ideas and politics so effectively" and why have subsequent ones had such difficulty doing so?

It is Mr. Wood's view that "as the common man rose to power in the decades following the Revolution, the inevitable consequence was the displacement from power of the uncommon man, the aristocratic man of ideas." As he sees it, "the revolutionary leaders were not merely victims of new circumstances; they were, in fact, the progenitors of these new circumstances": "They helped create the changes that led eventually to their own undoing, to the breakup of the kind of political and intellectual coherence they represented. Without intending to, they willingly destroyed the sources of their own greatness."

In short, the founding fathers helped unleash democratic and egalitarian forces that would put an end to "many of their enlightened hopes and their kind of elitist leadership." They "succeeded in preventing any duplication of themselves."

This is a variation, of course, on the central argument laid out in Mr. Wood's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1992 book, "The Radicalism of the American Revolution": namely, that the Revolution helped smother the patronage, paternalism and hierarchical relationships of the 18th century and usher in a new, democratic, capitalistic world; that it undermined the whole idea of aristocracy and elitist virtue and helped bring about a new society defined by the common man.

In this volume Mr. Wood tries to illustrate this thesis through a series of portraits of "American worthies" — including such seminal and highly familiar figures as Washington and Jefferson, and lesser, more controversial ones like Thomas Paine and Aaron Burr.

Though these chapters (many of which started out as magazine articles) are all erudite and shrewdly argued, they vary widely in their effectiveness and relevance to the author's central argument. A chapter contending that, contrary to popular belief, James Madison's thinking evinced a consistency throughout his career, is really a stand-alone essay, aimed more at other historians than at the lay reader.

And a chapter suggesting that John Adams was "cut off from the whirling broader currents of American thinking" and ultimately anachronistic in his views about the relationship between the government and the people willfully ignores the more prescient aspects of Adams's thinking, eloquently explicated in recent books by Joseph J. Ellis and David McCullough.

This volume is at its most powerful when Mr. Wood uses his enormous knowledge of the era to situate his subjects within a historical and political context, stripping away accretions of myths and commentary to show the reader how Washington, say, or Franklin (the subject of a 2004 book by the author) were viewed by their contemporaries. He explains how the reputations of these men waxed and waned over the years, and how changing ideological fashions in history writing have continually remade their images: most notably, how the current academic focus on gender, class and race issues has marginalized the study of politics and political leaders and contributed to the vogue for debunking "elite white males."

As Mr. Ellis did in his 2000 best seller, "Founding Brothers," Mr. Wood communicates the huge odds the revolutionary generation were up against in taking on the imperial power of Britain, and he also conveys the tumultuous, highly partisan mood of the 1790's, as the Federalists (led by Hamilton and Washington) clashed with the Republicans (led by Jefferson and Madison), and the legacy of the Revolution and the ramifications of the Constitution were debated.

In addition, Mr. Wood underscores the degree to which personality and personal philosophies informed these leaders' politics: how the realism (some might say pessimism) about human nature shared by Adams and Hamilton shaped their belief in the need for a strong government; how the optimism (some might say naïveté) about human nature held by Jefferson and Paine led them to see government as a threat to human liberty and happiness.

What most members of the founding generation shared, Mr. Wood argues, was a "devotion to the public good," a gentlemanly belief in the importance of disinterested public service, and a self-conscious seriousness about their duty to promote the common welfare.

Among the founding fathers' circle, one who did not share this outlook was Burr. As a senator from New York, Burr used "his public office in every way he could to make money," Mr. Wood says, and his "self-interested shenanigans" alarmed colleagues on both ends of the political spectrum. When the presidential election of 1800 was thrown into the House of Representatives, Hamilton — who would later be killed in a famous duel with Burr — "spared no energy" in persuading his fellow Federalists to support his longtime rival Jefferson over Burr; after more than 30 ballots in the House, Jefferson finally became president.

That bitter enemies like Hamilton and Jefferson joined forces against Burr, Mr. Wood writes, was an indication that they believed he "posed far more of a threat to the American Revolution than either of them ever thought the other did."

As Mr. Wood sees it, however, Jefferson and Hamilton, like the other founders, belonged to the past: in a "democratic world of progress, Providence and innumerable isolated but equal individuals, there could be little place for the kind of extraordinary political and intellectual leadership the revolutionary generation had demonstrated." It was Burr, he adds, who embodied "what most American politicians would eventually become — pragmatic, get-along men."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)